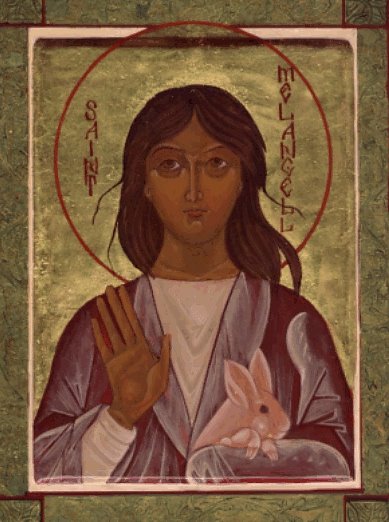

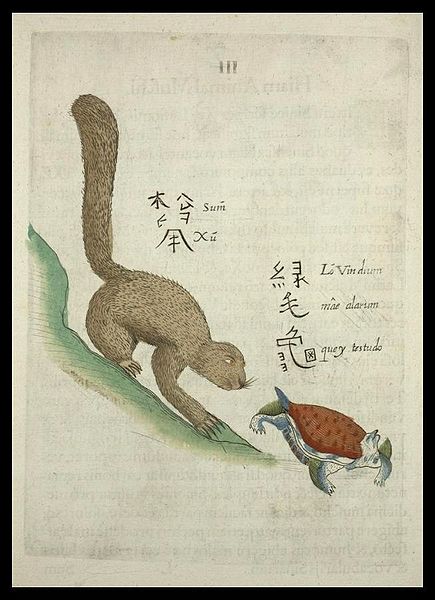

Sum Xu (松鼠)

Sum Xu animal apud Sinas reperitur, flavi & nigri coloris est, pulcherimi aspectus. Cicurant illiud Sinenses & collum argento exornant, mures egregiè venatur. Sæpe venit septem & novem scudis. ....

Lo Meo Quey (绿毛龟) - Vindium (viridium?) alarum Testudo

Alatæ testudines in aliquibus provinciis Sinarum & præcipuè in Ho-van inveniuntur virides, & interdum cæruleas adiunctas pedibus habet alas, & gradum tardissimum quàm volatu aut potiùs quodam saltu extensis pedum alis compensat. Pedes alati hujusmodi testudinum in pretio sunt apud Sinas etiam ob raritatem. ...

(Michael Boym, Flora Sinensis, 1656

While looking for later references to some of the creatures mentioned in Boym's work, I found an interesting article by Sarah Hartwell about a strange breed of cats that, according to many European authorities of the 18-19th centuries, supposedly existed in China - but was not anywhere to be found when people actually went looking for it. This certainly called for a day in a rare book library...

Polish Jesuit's squirrel

The Jesuit missionaries who operated in China between the late 16th and early 17th century were a an outstanding group, but even against this background the story of Michael (Michał) Boym (ca. 1612–1659) is remarkable. Born in Lwów (a.k.a Lemberg, Lvov, Lviv), he left his native Poland to join the Jesuits, and was posted to China. He happened to arrive to China right around the time of the Manchu invasion and the fall of the Ming Dynasty. Fifty years earlier, the Wanli Emperor never deigned to meet Matteo Ricci and Diego Pantoya in person (and when given the portrait of the priests, exclaimed "Ah, they are Hui-Hui!"). Now, when Beijing and Nanjing both fell to the Manchus, Koffler (another Jesuit, an Austrian) and Boym were able to enter the inner circle of the court of the Yongli Emperor (a grandson of Wanli), who was still resisting the Manchus from the empire's southwestern corner, and to baptize several members of the royal family. As the Ming's situation became increasingly precarious, Empress Elena sent Boym to Europe with a plea for help from the Pope. The Portuguese (who controlled Jesuit's operations in China and elsewhere in Asia) and the Jesuit leadership, however, were not all that enthusiastic about supporting the Ming's nearly-lost cause, so getting to Europe became yet another adventure for Boym and his traveling companion, a Chinese Christian named Andrew Zheng.

Engaged as he was with politics and the missionary business, Boym managed to write a few important books and articles, only some of which were published at the time. One of the best known is his delightful Flora Sinensis (1656). The album actually covered both flora and fauna, and not only of China. One of the most interesting pictures there was the one showing two creatures: Sum Xu (松鼠) and Lo Meo Quey (绿毛龟).

松鼠 is transcribed songshu in the modern Chinese transcription (Hanyu Pinyin), and is the usual Chinese word for "squirrel". (The literal meaning is "pine rat".) ''Sum Xu'' would be the normal way to transcribe this in the Portuguese-influenced transcription that Boym used; elsewhere, for example, he has the Shandong province as Xantum. While Boym's picture of the creature is reasonably squirrel-like, his description of the creature's lifestyle is, however, decidedly non-squirrel-ly. According to Boym, the ''sumxu'' was a pretty yellow-and-black animal, commonly tamed, and made to wear silver a collar. Valued as good hunters of mice, they would sell for 7 to 9 silver coins. Based on this, it has been suggested (e.g., by Hartmut Walravens) that he was actually describing some animal from the mustelid family (including martens, ferrets, weasels, etc.) that may have been domesticated in China.

Boym's treasure trove of flora and fauna became further popularized in Europe via the efforts of another Jesuit, German Athanasius Kircher. Early in his career, Kircher, too, wanted to become a missionary and go to China, but instead he became a professor in Rome, and published an astonishing number of books. The one that concerns us is his ''China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis naturae and artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata'' (1667). Making heavy use of the expert help provided by Boym, Martino Martini (Kircher's former student, and now an important Jesuit visiting Europe from China), and Zheng, the book was able to break new ground in European Sinological literature - for example, the transcript and translation of the Nestorian Stele of Xi'an was probably the first Chinese document of a comparable size published in Europe in original and translation.

But Boym and Martini had to go back to China after a few years in Europe; once on his own, Kircher was to rely much heavier on his imagination throughout the rest of his book. His description of the ''sumxu'' was, however, fairly close to Boym's original:

There is also a domestic animal called the Sumxu which is similar to a cat. It is black and saffron colored and has splendid hair. The Chinese tame it and put a silver collar around its neck. It is an avid hunter of mice. It is so rare that one sells for seven to nine scudi.(p. 186, in modern English translation by Dr. Charles D. Van Tuyl), although it is Kircher, not Boym, who was the first to compare the creature to a cat.

Kircher, however, seemed to have given free rein to the fantasy of the artist who was to provide a picture of the animal. While the body shape of the creature is much like the one in Boym's picture, it is Kircher's picture that gave us a scale: his ''sumxu'' looks almost as long as the two men next to it are tall. Through the open door in the back of the room one can see a hunter with a few similar creatures chasing a deer (rather than mice, as the text says!) No wonder that a later art historian described the curious creature as a "Chinese badger"!

The caption in Kircher's book is rather curious too. As Szczesniak notes at some point, Boym's Chinese handwriting was competent enough, but fairly clumsy, as it is common with foreigners learning Chinese. Kircher's artists obviously did not know Chinese at all, so he mangled Boym's Chinese caption in a curious way: the two-character word 松鼠 (which Boym's writes in a vertical way) has now been split into three nonsensical character arranged from the left to the right. The left half of 松 (i.e., the 木 radical) and the left top corner of 鼠 now make up the first "character" of Kircher's caption; the right half of 松 (i.e., 公, which was already written by Boym rather clumsily) and the right top corner of 鼠 are making the last "character" of Kircher's caption; and the remaining part of 鼠 is its middle character. Above the pseudo-Chinese text a strange inscription in Latin characters says: Feki. This word does not occur in the text of the book itself (nor, needless to say, in Boym), and I am at a complete loss as to where the artist got it from. Most likely, from the thin air... although, possibly, the artist read an anagram of these letters into the Chinese character 鼠.

Boym's winged turtles made an appearance in Kircher's book as well, but that's a story for another day.

Martini's white cats of Peking

Michael Boym was not the only Jesuit visit Europe from China in the 1650s. Another person whose reports made a sensation throughout Europe's literati at the time was Martino Martini. Originally from Trent (now in northern Italy), Martini was overtaken by the advance of the Manchus while in east-central China, and was able to switch his loyalty to the country's new masters smoothly enough. He was sent to Europe by the China-based Jesuit organization to advocate the mission's policy of "accommodation" to the Chinese realities (controversial with some Catholic circles in Europe).

During his European trip, Martini published Novus Atlas Sinensis (1655), which besides maps, contained a fairly detailed description of each of China's provinces. In the section on the Peking Province, also known as Northern Zhili (which included Beijing, Tianjin and what's today the Hebei Province), Martini talks about white, long-haired and long-eared cats found there (p. 22):

Feles in deliciis

Feles in hac Provincia sunt omnino albæ, longioribus pilis protensisque auriculis, qui canum Melitensium habentur loco, matronarumque sunt deliciæ : at mures minime capiunt, forte quia delicate nimis à dominis suis enutritæ, haud tamen desunt etiam aliæ murium egregiæ venatrices, licet minus laute habitæ, eoque forte meliores.

Martini's Atlas became the authortiative source on China's geography for the next 80 years, and his descriptions were often copied wholesale by other authors. A compilation "Englished" in 1673 by John Ogilby[1] has two passages based on Martini's white cats story. On page 98, in the description of the Northern Zhili (Province of Peking that's inserted into the Johannes Nieuhoff's report, he has:

In this Province are white rough cats, not unlike the Malteeza Dogs, with long Ears, which are there the Ladies Fosting-hounds or Play-fellows; they will catch no Mice, being too much made of: There are other Cats that are good Mousers, but they are very scarce, and had in great esteem.And then in Chapter XVI, "Of Animals"; page 233:

In the province of Peking there are some Cats with very long hair, as white as Milk, and having long Ears like a Spaniel: the Gentlewomen keep them for their Pleasure; for they will not hunt after, or catch Mice, the reason perhaps being for that they are too high fed: Yes they have store of other Cats which are good Mousers.

Martini's long-eared cats, now compared to a spaniel, kept living in European literature about China. In 1736-37, his Atlas was to a large extent superseded by the multi-volume Description de l'Empire de la Chine, compiled in Paris by the Jesuit du Halde. While the work was primarily based on teh reports on over a dozen French Jesuits who had worked in China over the several preceding decades, the overall framework, and quite a bit of the content had come from Martini. And sure enough, in the "Pe Tche Li" (i.e., Northern Zhili) section of Volume 1 of du Halde's work, page 134, we find a nearly verbatim copy of Martini's report. The only things that's lost are the mention of the cats' white color, and their disinclination to catch mice:

Parmi les animaux de toute espèce, on y trouve des chats singuliers, que les Dames Chinoises recherchent fort, pour leur servir d'amusement, & qu'elles nourissent avec beaucoup de délicatesie : ils ont le poil long, & les oreilles pendantes.

Around du Halde's time, the ability of Europeans to do on-the-ground research in China became severely curtailed, due to deteriorating relations between the Catholic church and the Chinese authorities. No wonder that du Halde's book remained the standard reference for the next century. The China chapters in ''A new general collection of voyages and travels'' (compiled by John Green. London : T. Astley, 1745-47), were pretty much an abbreviated ranslation of du Halde's, and the section on "Pe-che-li, Cheli, or Li-pa fû, the first province" (page 6), stated:

Among the animals, there is a particular Sort of Cats, with long Hair, and hanging Ears, which the Chinese Ladies are very fond of.John Green's compilation was back-translated into French by abbé Prevôt (a.k.a. Prévost d'Exiles). In Vol. IV, ''Geographie de la Chine'', of Prevôt's ''Histoire générale des voyages'', we read (Paris, 1748), the chapter on "Province de

Entre les animaux, on vante une espece singuliere de chats à long poil, avec des oreilles pendantes, que les Dames Chinoises aiment beaucoup.

Buffon and his work of synthesis

It was, however, the great French naturalist Georges Louis Leclerc (Comte de Buffon) who brought the ''sumxu'' and the long-eared cat from the realm of general geography and into that of "natural science". He noticed that cats have a lot fewer distinct breeds than dogs, and thought that only Spain, Syria and Khorasan (i.e., Persia) have developed truly distinct cat breeds; the purported long-haired lop-eared cat of Northern Zhili could perhaps be the fourth:

Ils sont en effet d’une nature beaucoup plus constante, et comme leur domesticité n’est ni aussi entière, ni aussi universelle, ni peut-être aussi ancienne que celle du chien, il n’est pas surprenant qu’ils aient moins varié. Nos chats domestiques, quoique différens les uns des autres par les couleurs, ne forment point de races distinctes et séparées ; les seuls climats d’Espagne et de Syrie, ou du Chorazan, ont produit des variétés constantes et qui se sont perpétuées : on pourroit encore y joindre le climat de la province de Pe-chi-ly à la Chine, où il y a des chats à longs poils avec les oreilles pendantes, que les dames Chinoises aiment beaucoup.(Histoire Naturelle, vol. 6, p. 14, or p. 670 in this later edition)Buffon (1777) gave as his source the work of abbé Prevôt, which, as we know, was the French back-translation of John Green's digest of du Halde's Description... whose cat reference, in its turn, goes back to Martini (1655)!

Buffon was good at building general theories of... of everything. He observed that in the process of the development of the domestic dog breeds, wolves' stiff standing ears often evolved into softer, hanging ears, and surmised that this applied to cats as well. He though that the wild cats have "stiffer" ears than the domestic ones, and of course it was only so natural that in a country of ancient civilization and "mild climate" such as China cats would have a chance to develop hanging ears (sort of like the Pekingese dog):

Les chats domestiques n’ont pas les oreilles si roides que les chats sauvages, l’on voit qu’à la Chine, qui est un empire très-anciennement policé et où le climat est fort doux, il y a des chats domestiques à oreilles pendantes. (''Histoire Naturelle'', vol. 6, p. 17)

Buffon's Histoire Naturelle was meant to be all-encompassing; so we should not be too surprised that on p. xxxv the subject index (Table des matières) of Volume IX (supplément à l'Histoire des Animaux quadrupedes; 1777), between les SOURIS blanches aux yeux rouges (white mice with red eyes) and SURIKATE (meerkat), we find our old acquaintance, le SUMXU, not heard of since the days of Kircher more than a century before:

SUMXU (le) - eft un joli animal domestique à la Chine, qu'on ne peut mieux comparer qu'au chat. Notice à ce sujet. Volume VIII, 186.

And in the supplement to his chapter on Cats (Buffon 1777 - Vol. VIII, pp. 186-187; also seen here) Buffon performs his tour de force of synthesis, suggesting that perhaps the by-now-famous "lop-eared cat of China" is a different species from the regular domestic cat - and could not it be that mysterious ''sumxu''?

Nous avons dit (volume VI, page 14) qu’il y avoit à la Chine des chats à oreilles pendantes ; cette variété ne se trouve nulle part ailleurs, et fait peut-être une espèce différente de celle du chat, car les Voyageurs parlant d’un animal appelé Sumxu, qui est tout-à-fait domestique à la Chine, disent qu’on ne peut mieux le comparer qu’au chat avec lequel il a beaucoup de rapport. Sa couleur est noire ou jaune, et son poil extrêmement luisant. Les Chinois mettent à ces animaux des colliers d’argent au cou, et les rendent extrêmement familiers. Comme ils ne sont pas communs, on les achette fort cher, tant à cause de leur beauté, que parce qu’ils font aux rats la plus cruelle guerrea.

In retrospect, we understand that there was no particularly good reason to associate Boym's sumxu and Martini's long-eared cat. In fact, just the opposite:

- Sumxu was black-and-yellow, while for Martini one of the special features of those peculiar cats of Peking was their all-white fur. (As we have seen, the whiteness was one of the elements of Martini's report that was lost by the time of its being related by du Halde).

- Boym's picture of sumxu seems to completely ignore the creature's ears, while the long ears were a distinct feature of Martini's cat of Peking.

- Sumxu was valued as a good mice-hunter, while Martini specifically describes the long-eared cats asnot interested in mice. (Again, this point was omitted by du Halde).

- Boym did not compare the sumxu to cats (and, in fact, his picture looks a lot more like a squirrel than a cat!); it was Kircher who did, probably long after Boym left for China again.

- Boym's ''Flora Sinensis'' was primarily based on his observations in South China (note the abundance of tropical plants and animals there), while Martini specifically describes his white long-eared cats as a specialty of the Peking Province (a.k.a Northern Zhili), in the north of China.

While Buffon just suggested a connection between the sumxu and the lop-eared cat of Peking, some of the later authors who drew on his work described that connection as a certain fact. Thus, one Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest in his Mammalogie ou description des espèces de mammifères (Volume 1, p. 233) simply combined sumxu's name and color with the supposed Peking's cat location, hair texture, and "hanging ears". His list of the cat varieties of the world thus included, under no. 2:

... le chat d'oreilles pendantes, à poil fin and long, noir ou jaune, en domesticité à la Chine, dans la province de Pe-chi-ly, sous le nom de sumxu.

Accepted fact

"Cat Handlers and Tea Dealers of Tong-Chou", from China, The Scenery, Architecture, and Social Habits of That Ancient Empire (1843), based on sketches by William Alexander, who visited China in 1793. Although the scene is on the outskirts of Beijing, there is not a lop-eared cat in sight.

Blessed by Buffon's authority, the supposed existence of the lop-eared cat of Peking (its whiteness having been already forgotten) became an "accepted fact" for the authors of the 19th century biology books, from Brehm to Darwin, and especially those of cat books. From a specialty of the Peking province, the supposedly existence creature would often be transformed into simply "the cat of China". Sarah Hartwell cites a number of typical passages in her article; I will quote here just one, Le chat: histoire naturelle, hygiène, maladies by Gaston Percheron (1885). The author suggests that perhaps the lop-eared cat is a hybrid of a cat and a marten (pp. 127-128):

Certains naturalistes dignes de foi prétendent même qu'il [le chat domestique] s'accouple avec la fouine et qu'il produit alors des rejectons rappelant assez bien le dernier type par la couleur de pelade. C'est ainsi qu'ils expliquent chez le chat de Chine ces oreilles tombantes qui jurent si fort avec les formes traditionnelles de l'espèce.As in Martini and du Halde, the "cat of China" is still fed on choice morsels. But instead of merely being the pet of its doting mistress (as in these early works), the silky-furred and lop-eared ("like a badger") cat has been transformed, by Percheron's pen, into a delicacy itself, akin to swallow nests (p. 130):

Le Chat de Chine. Il a le poil long et soyeux et les oreilles pendantes, comme celles du blaireau.Sa chair est très estimée par les habitants du Céleste Empire. De même que le chien, il est de la part de certains nourrisseurs et engraisseurs de ce pays l'objet d'une sollicitude toute particulière. Et, quand il est bien en chair, il figure à côté des nids d'hirondelles sur les tables bien servies.

Reality check

After the Opium Wars, China became "opened" to foreign missionaries, entrepreneurs, and researchers. Quite a few of them undertook a search for the mysterious lop-eared cat. But, as the famous biologist and Catholic priest Armand David concluded in his report on China's wild and domestic felines (Les Missions Catholiques, Vol. 21; p. 227) (1889), there was none to be found:

Jamais nous n'avons rencontré la race à oreilles tombantes dont on a parlé beaucoup, il y a quelque temps.

Conclusions

At least my fur is white and silky!

Was Boym told a tall tale about mice-hunting squirrels? Did he mistakenly attach the name of a squirrel (songshu) to actually existing tamed martens (or similar animals)? (Misunderstandings like this did occasionally happen; see the note on his "winged turtles", to appear.) Was the word songshu (normally meaning "squirrel") actually applied to marten-like small predators in some remote region that he visited while evading the Manchu invaders?

What did Martini mean by his feles ... protensisque auriculis? He certainly could see white and silky-haired cats in Beijing wealthy homes, and of course there were Pekingese dogs with their hanging ears. Not that I claim that he took a Pekingese for a cat, but he wrote the text for his Atlas during a long, long grueling trip from China to the Netherlands by the way of Java and Norway... There was always space for a slip of the pen.

What I think we do know for sure is that Martini's story, and to a lesser extent Boym's, were copied (and sometimes merged) by dozens of authors for over two centuries, without anyone being in a position to verify them. Which probably is not all that unusual.